By Stuart Lambert, co-founder

What is the role of a company today when it comes to the impact it has on people and planet?

Companies must do two things. They must first reduce negative impacts from the business. This, fundamentally, is the agenda of ESG: managing risks not just to but from the business.

Companies must also consider their capability to creative positive impact. That is really the essence of the frequently misused term, Purpose: doing measurable good for society and the environment on which society depends.

Companies need to be fulfilling both sides of the impact equation: minimising harms and maximising good, two ideas that are often conflated but are two quite different things requiring their own measurement.

When it comes to measurement, the ‘reducing harm’, ESG side of things is characterised by target-setting. The “net-zero date” is of course the most totemic example. There are others, and they are always about reducing something. Emissions. Water usage. Packaging. Forced labour.

Because of the regulatory scrutiny on this side of things, these negative impact reduction targets are – if they are to be credible – backed up by robust delivery plans, clear methodologies, and real accountability in terms of reporting.

But when it comes to the ‘positive impact’ side of the equation we don’t see anything like the same rigour. For all the progress in ESG reporting, in terms of data and detail, when it comes to Purpose comms, reporting on the positive impact a company has, a lot of it still looks like old-fashioned CSR.

Spending abstract amounts of money on charitable projects not for any strategic reason, or because of a committed impact agenda, but because it feels like the right thing to do. And because it’s good for reputation and brand.

This is a missed opportunity, and a risk.

There is a serious risk that ESG is getting to a point where it feels like – or IS – just too much data to process, risk assess and manage effectively. (ESRS alone requires reporting against 1,100 new data points.)

And there’s therefore the risk that the story you want to tell as a company, as a brand, drowns in a sea of data. That the company ends up being defined by how effectively it can prove to the world that it is mitigating the potential to cause harm. Leaving very little attention bandwidth remaining to prove to the world that you have a positive impact on people and planet.

And let’s be clear. It is on the positive impact side of the equation that you can differentiate your business and brand. Reducing emissions and packaging – these are table stakes. It is very hard to differentiate your brand on this stuff.

Because “I’m really excited about brand X’s emissions reduction strategy,” was said by nobody, ever.

“Because ‘I’m really excited about brand X’s emissions reduction strategy,’ was said by nobody, ever. ”

Consumers are never going to get excited about your water efficiency measures, or your packaging recycling figures. They may well rationally care, and say they care when asked about it in a survey, but emotional engagement? Let’s get real.

People do get excited about and inspired by the positive difference you make to the world, however.

Think of the outpouring of emotion at the apparent demise of The Body Shop: that wasn’t because of brilliant products or customer service but because we believed The Body Shop was special, it was different. It stood for something positive. It did some real good in the world.

Think of James Timpson’s work with ex-offenders: incredible positive human impact. Think of Patagonia. Think of Ben and Jerry’s. Think of disruptive impact startup brands like Who Gives A Crap. Proving and celebrating your positive impact is what will win hearts and minds – and wallets.

Our research has shown that there is one thing that real impact leaders do better than their competitors. One thing that pulls their impact strategy together most compellingly, and cost-effectively.

And it is the creation of an ambitious, unifying positive impact target or goal. We call this an Anchor Goal© and we define it as: “An ambitious but credible and quantifiable target that ‘anchors’ your impact narrative. It specifies positive impact not harm reduction. And it should reinforce the company’s commercial strategy. “

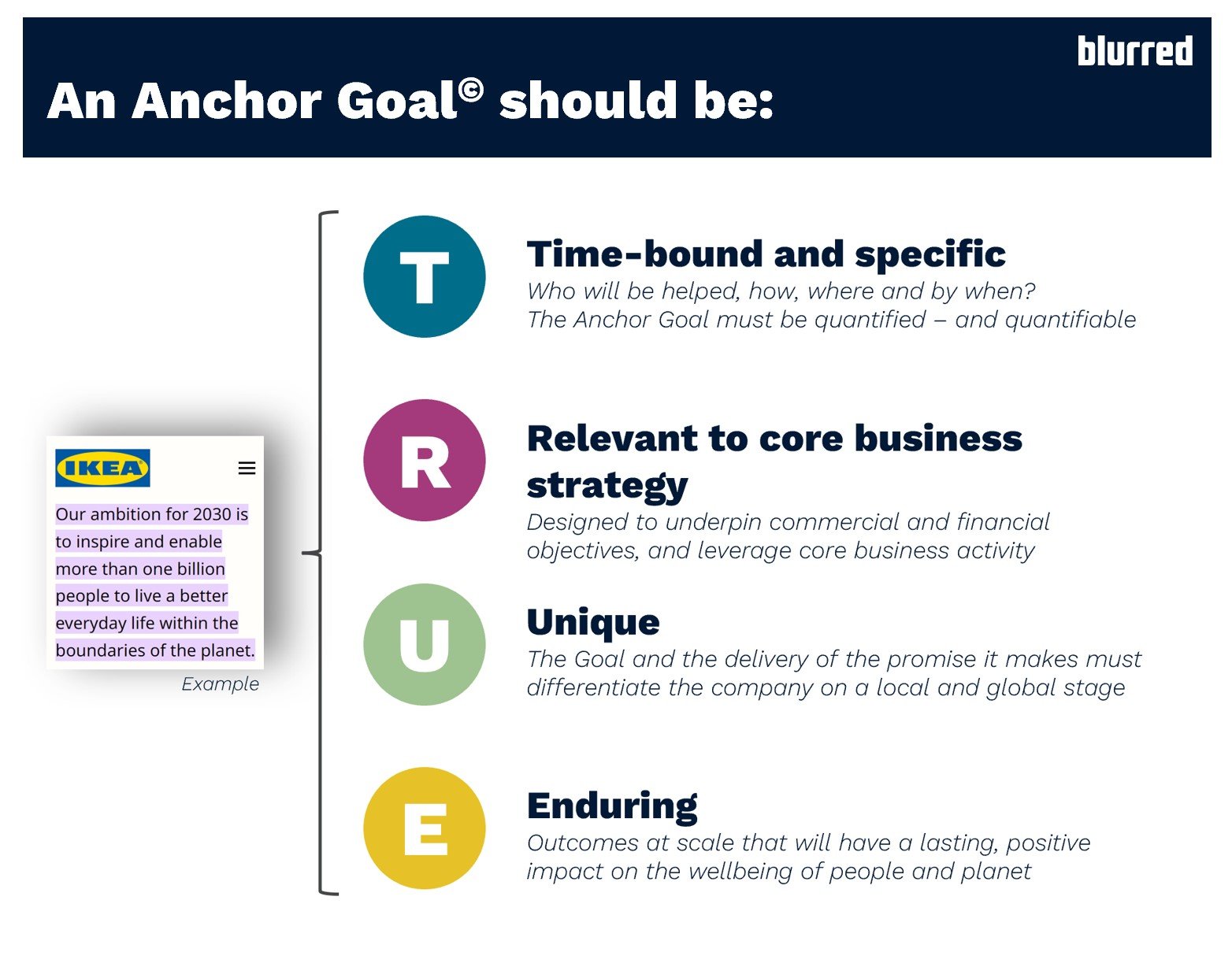

We’ve developed TRUE, a framework for identifying and codifying that anchor goal. The TRUE criteria underpin a methodology for helping companies create a credible and differentiating Anchor Goal and then put it at the heart of their impact strategy.

IKEA is a good example of a company which is doing this really well. A great goal that is deeply connected to the company’s commercial strategy, its brand, its business model, in terms of transforming manufacturing and delivery processes to support circularity.

Other notable examples include Mastercard and Bayer.

The former’s is a great example of an anchor goal that ties directly to the business strategy of being the #1 payment provider for small businesses, and which focuses on a material S issue, the empowerment of women in small businesses.

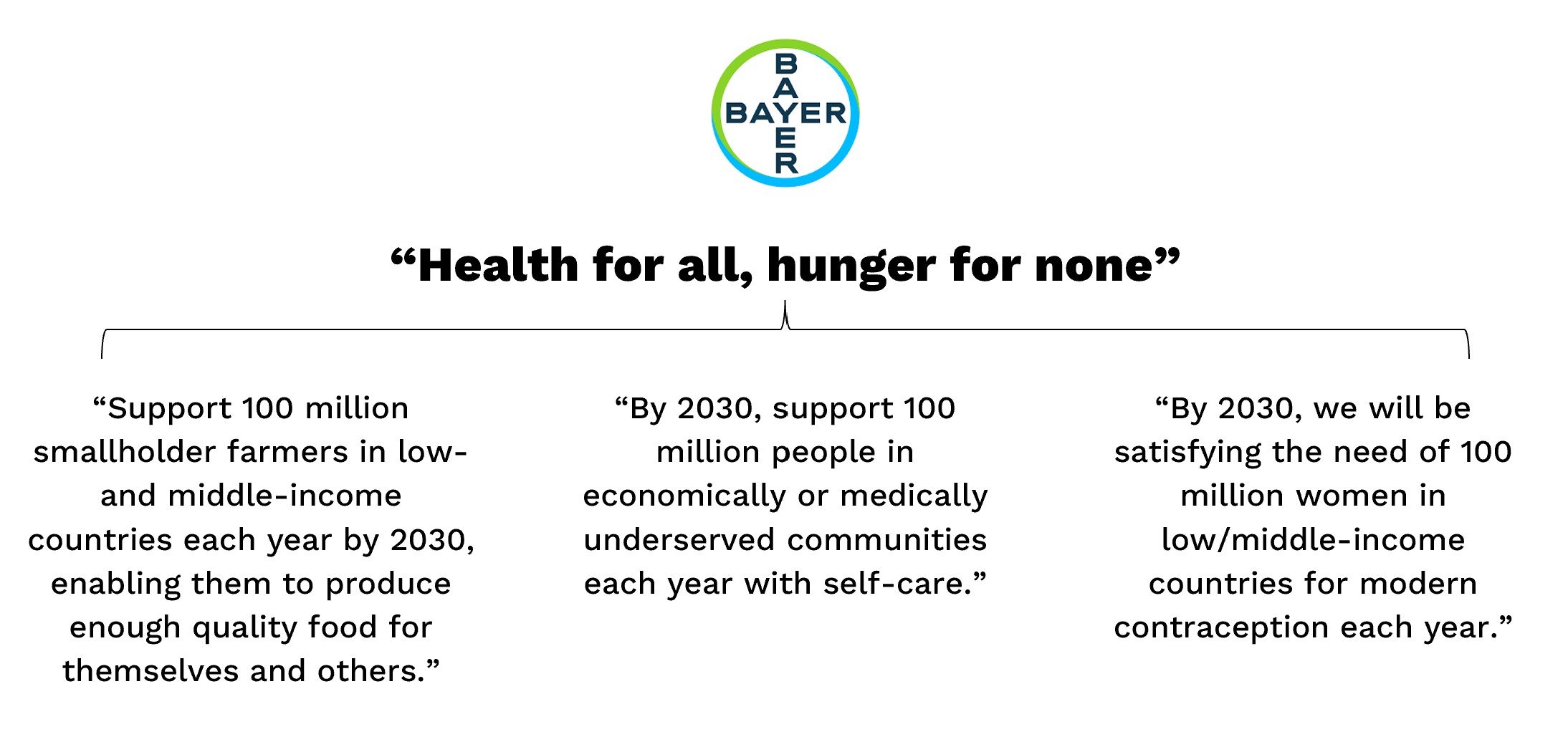

Bayer has more than one specific, ambitious, quantifiable positive impact goal, each of which underpins a core pillar of the business’s overall commercial strategy, spanning its diverse sector footprint (crop science, pharmaceuticals and consumer health).

But these examples are rare. At least among multinational businesses – businesses of scale and therefore having the greatest capacity to affect meaningful change, fast.

That needs to change if we’re to avoid missing the opportunity here to make a difference and do so in a way that’s properly commercial. Companies and brands have to instead seize that opportunity. And move from an ‘ESG-only’, harm reduction mindset to a more holistic ‘net impact’ mindset. Focusing not ONLY on harm reduction but on something positive and inspiring: doing good. Reconciling ESG and sustainability with commerciality and business growth.

In terms of comms and marketing, that’s what really engages people, emotionally. Positive storytelling, about the positive actions you are taking, and the positive outcomes you are driving.