Brianne Riewer, Junior Consultant, explores “pink pill” trends on social media and how brands should engage.

Earlier this year, Adolescence sparked widespread conversations about the influence of ‘red-pill ideology’ and toxic masculinity on young men.

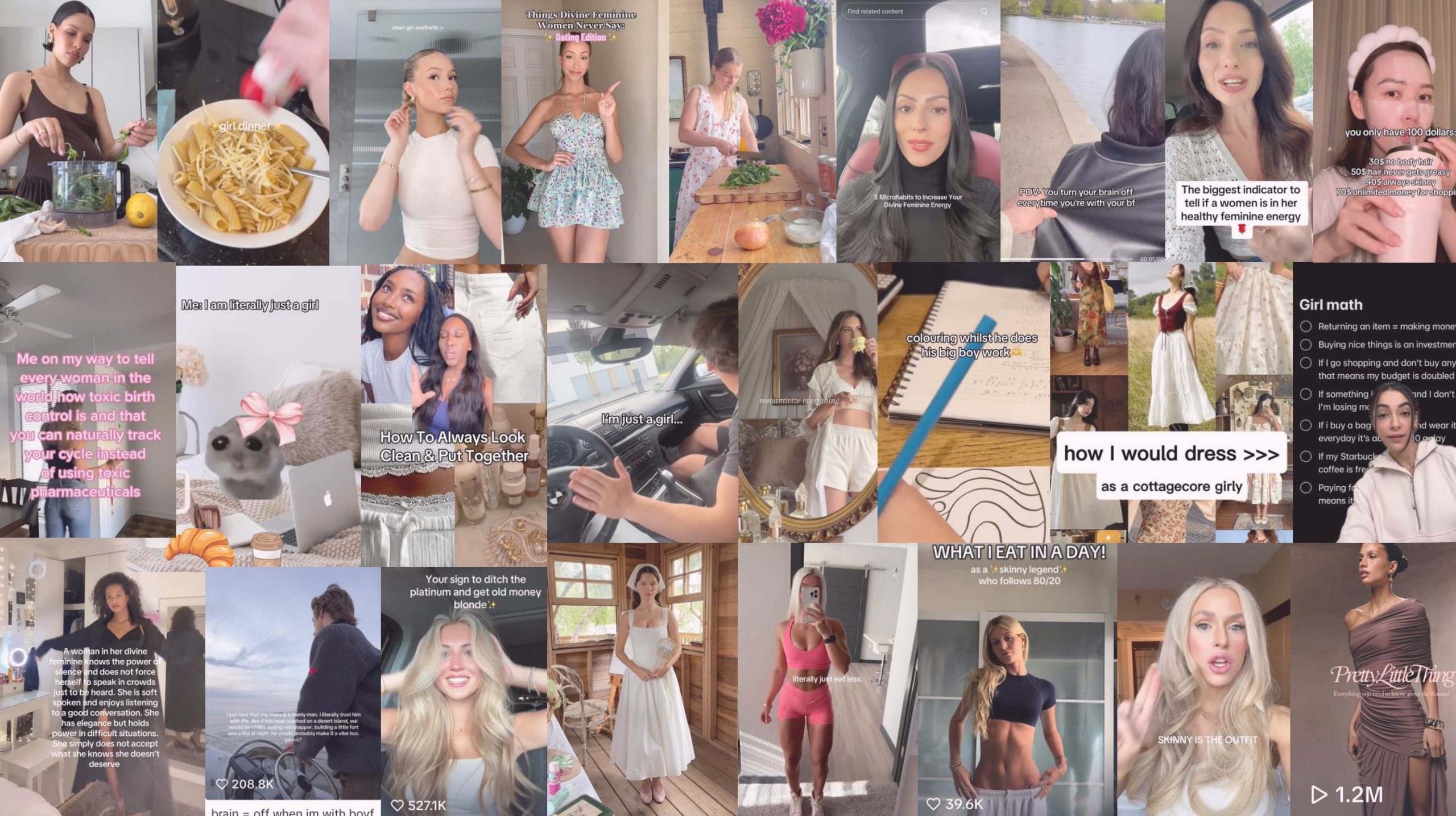

Though the focus on boys is needed, the current discourse misses the point that content targeting young women often echoes the same ideologies pushed by Andrew Tate et al, made more palatable and subtle by the different format in which it is presented. And whilst few brands would engage with a male influencer promoting incel culture, the packaging of these same ideologies for a female audience make it more likely that brands could unwittingly feed into these dangerous tropes.

The tradwife trend is the most overt content steering women to a conservative ideal. To be clear, a woman baking bread for her husband is not a threat to feminism and there’s nothing harmful about domesticity in isolation.

However, when they become part of a larger ideological framework that idealises submission and erases autonomy, we enter more dangerous territory.

Tradwife influencers curate aspirational identities, often without acknowledging the broader context, which paints the past as a simpler and safer time – a common tactic of the far right – despite this being starkly untrue for many groups.

That same sense of nostalgia threads through other trends like the cottagecore, clean girl, and old money aesthetics. All of them, in different ways, push a lifestyle that is racially coded and economically inaccessible, whilst linking femininity with modesty and domesticity, inadvertently promoting power structures which can cause real life harm.

Divine femininity is often sold as a spiritual framework that encourages softness, surrender, and intuition. It can appear in tandem with the soft living or soft girl trend. I’ve often come across it in the form of dating advice and self-improvement.

The logic goes like this: if you’re not attracting the right kind of man, you must be too masculine. To fix this, you need to tap into your feminine by being less vocal and less demanding. This is framed as innate to a women’s biology, normalising restrictive ideas of womanhood.

“I’m just a girl.” “Girl dinner.” “Girl maths.” These viral phrases have taken over Gen Z’s online and real life discourse. At first glance they’re light-hearted, but collectively, they turn women into regressive caricatures. Women see themselves as unserious and incompetent, using themselves as the butt of an age-old joke. While that might feel funny or relatable, over time, it sticks and only serves to reinstate misogynistic beliefs.

As communicators and brand guardians, we are not passive observers. Our industry helps to shape culture and choose which ideas to amplify.

PrettyLittleThing, for example, has pivoted from bold party-girl fashion to modest, hyper-feminine looks in a move that feels like a rebrand of traditional values.

The question is: should brands simply follow the algorithm and ride whatever trend gains traction, like PrettyLittleThing? Or is there an opportunity to take an active role in the conversation, and support young people to navigate this complex online world?